http://www.theatlantic.com/culture/...jacksons-unparalleled-influence/58616/Michael Jackson's Unparalleled Influence

Jun 24 2010, 11:37 AM ET | Comment

Michael Jackson was the most influential artist of the 20th century. That might sound shocking to sophisticated ears. Jackson, after all, was only a pop star. What about the century's great writers like Fitzgerald and Faulkner? What about visual artists, like Picasso and Dali, or the masters of cinema from Chaplin to Kubrick? Even among influential musicians, did Michael really matter more than the Beatles? What about Louis Armstrong, who invented jazz, or Frank Sinatra, who reinvented it for white people? Or Elvis Presley, who did the same with blues and gospel, founding rock in the process? Michael Jackson is bigger than Elvis? By a country mile.

First, there is no question that musicians in the 20th century had far more cultural impact than any other sort of artist. There is no such thing, for instance, as a 20th-century painter that is more famous than an entertainer like Sinatra. There are no filmmakers or movie stars that had more cultural sway than The Beatles, and no 20th-century writers who touched more lives than Elvis. Consider that thousands of human beings, from Bangkok to Brazil, make their living by pretending to be Elvis Presley. When was the last time you saw a good impression of Picasso? Even Elvis, though, is overshadowed by Jackson's career.

First, with the possible exception of Prince and Sammy Davis Jr., Michael Jackson simply had more raw talent as a performer than any of his peers. But the King of Pop reigns as the century's signature artist not just because of his exceptional talent, but because he was able to package that talent in a whole new way. In both form and content, Jackson simply did what no one had done before.

Louis Armstrong, for instance, learned music as a live performer and adapted his art for records and radio. Sinatra and Elvis were also basically live acts who made records, ultimately expanding that on-stage persona into other media through sheer force of charisma. The Beatles were a hybrid; a once-great live band made popular by radio and TV, forced by their own fame to become rock's first great studio artists.

Jackson, though, was something else entirely. Something new. Obviously he made great records, usually with the help of Quincy Jones. Jackson's musical influence on subsequent artists is simply unavoidable, from his immediate followers like Madonna and Bobby Brown, to later stars like Usher and Justin Timberlake.

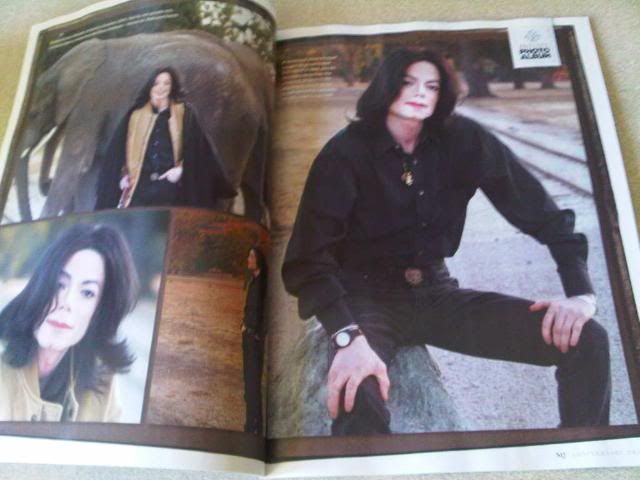

Certainly, Jackson could also electrify a live audience. His true canvas, though, was always the video screen. Above all, he was the first great televisual entertainer. From his Jackson 5 childhood, to his adult crossover on the Motown 25th anniversary special, to the last sad tabloid fodder, Jackson lived and died for on TV. He was born in 1958, part of the first generation of Americans who never knew a world without TV. And Jackson didn't just grow up with TV. He grew up on it. Child stardom, the great blessing and curse of his life, let him to internalize the medium's conventions and see its potential in a way that no earlier performer possibly could.

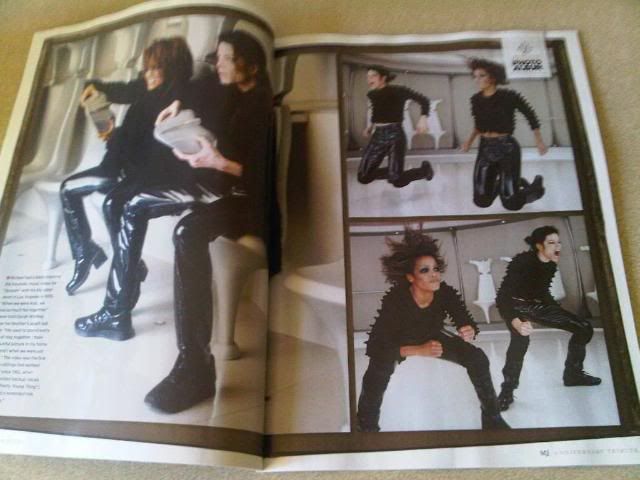

The result, as typified by the videos for "Thriller," "Billie Jean," and "Beat It," was more than just great art. It was a new art form. Jackson turned the low-budget, promotional clips record companies would make to promote a hit single into high art, a whole new genre that combined every form of 20th century mass media: the music video. It was cinematic, but not a movie. There were elements of live performance, but it was nothing like a concert. A seamless mix of song and dance that wasn't cheesy like Broadway, it was on TV but wildly different from anything people had ever seen on a screen.

The oft-repeated conventional wisdom—that Jackson's videos made MTV and so "changed the music industry" is only half true. It's more like the music industry ballooned to encompass Jackson's talent and shrunk down again without him. Videos didn't matter before Michael, and they ceased to matter at almost the precise cultural moment he stopped producing great work. His last relevant clip, "Black or White," was essentially the genre's swan song. Led by Nirvana and Pearl Jam, the next wave of pop stars hated making videos, seeing the entire format, and the channel they aired on, as tools of corporate rock.

The greatest impact of the music video wasn't on music, but video. That is, on film and television. The generation that grew up watching '80s videos started making movies and TV shows in the '90s, using MTV's once-daring stylistic elements like quick cuts, vérité-style hand-helds, nonlinear narrative and heavy visual effects and turning them into mainstream TV and film movie conventions.

If Jackson had only been a great musician who also invented music video, he still wouldn't have mattered as much. Madonna, his only worthy heir, was almost as gifted at communicating an aesthetic on-screen. The aesthetic Jackson communicated, however, was much more powerful, liberating and globally resonant than hers. It was more powerful than what Elvis and Sinatra communicated, too. Hence, that whole "Most Influential Artist" thing.

American popular music has always been about challenging stereotypes and breaking down barriers. Throughout the century, be it in Jazz, Rock or Hip-Hop, black and white artists mixed styles, implicitly, and often explicitly, advocating racial equality. Popular music has always challenged sex roles, too. Top 40 artists especially, from Little Richard and proto-feminist Leslie Gore, to David Bowie, Madonna and Lady Gaga have pushed social progress by bending and breaking gender rules.

Jackson was clearly a tragic figure, and his well-documented childhood trauma didn't help. But his fatal flaw, and simultaneously the source of his immense power, was a truly revolutionary Romantic vision. Not Romantic in the sappy way greeting card companies and florists use the word, but in its older, Byronic sense of someone who commits their entire life to pursing a creative ideal in defiance of social order and even natural law. Jackson's Romantic ideal, learned as a child at Motown founder Berry Gordy's feet, was an Age of Aquarius-inspired vision using of pop music to build racial, sexual, generational and religious harmony. His twist, though, was a doozy.

He not only made art promoting pop's egalitarian ethos, but literally tried embody it. When that vision became an obsession, a standard showbiz plastic surgery addiction became something infinitely more ambitious—and infinitely darker. Jackson consciously tried to turn himself into an indeterminate mix of human types, into a sort of ageless arch-person, blending black and white, male and female, adult and child. He was, however, not an arch-person. He was just a regular person, albeit a supremely talented one, and time makes dust of every person, no matter how well they sing. Decades of throwing himself against this irrefutable wall of fact ravaged him, body then soul, and eventually destroyed him.

At his creative peak, though, it almost seemed possible. Michael could be absolutely anything he wanted; Diana Ross one day, Peter Pan and the next. Every breathtaking high note, every impossible dance-step and crazy costume projected the same message. There are no more barriers of race, sex, class or age, he told his audience. You, too, can be and do whatever you want. We are limited only by our power to dream. A performer who can make you believe that, to feel it, even for a moment, comes along once in a lifetime. Maybe. If you're lucky.

As years pass and history sanitizes his memory, Jackson's legend will only grow. One day, in addition to being the most influential artist of the 20th century, he may well topple Elvis become the most-impersonated as well. Jackson, after all, only died a year ago. Elvis has been gone since 1977. Another two or three decades and Michael might have the most impersonators from Bangkok and Brazil. Let's just hope that they don't take it too far.