By Chuck Yarborough, Mar 21, 2019

Cleveland.com

CLEVELAND, Ohio – To be considered for the

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, a band has to have put out recorded music at least 25 years earlier.

With that in mind,

Roxy Music’s

eligibility is just about old enough to be eligible for the Rock Hall, so there’s a certain degree of “about time” in the induction of the influential British band as a member of the Class of 2019.

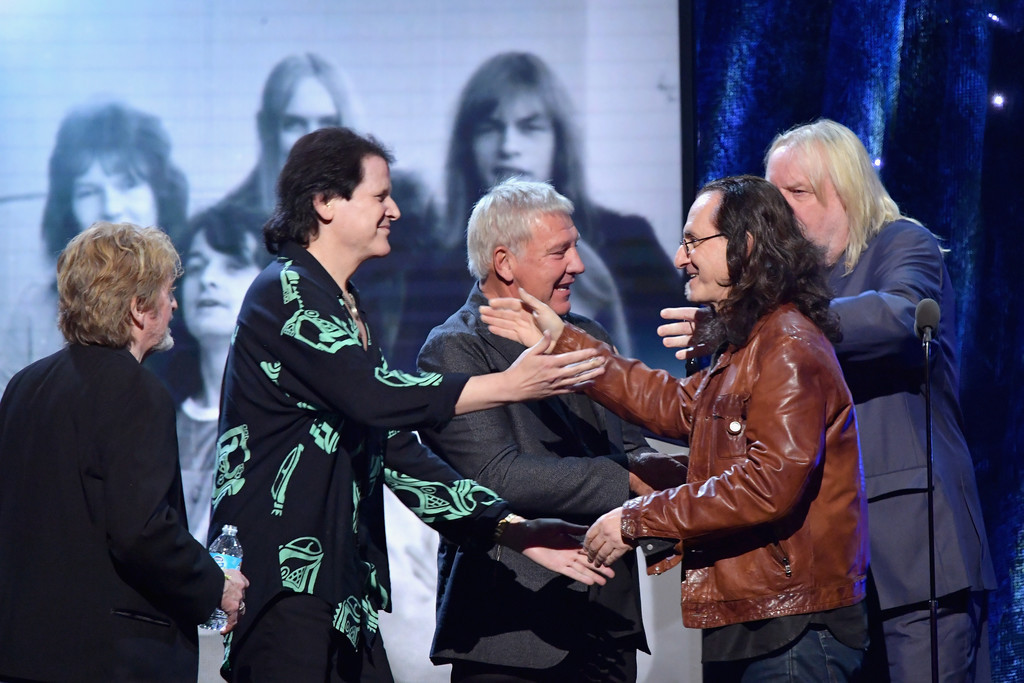

Bryan Ferry and his band, including Brian Eno, Andy Mackay, Phil Manzanera, Eddie Jobson and Paul Thompson, made it into the Rock Hall their first time on the ballot, a travesty considering the group that’s considered one of the founders of “glam rock” (a phrase Ferry dislikes) first qualified for membership in 1997.

In 2013, the website

utimateclassicrock.com put it pretty well in discussing the group’s most prominent era, from 1972 to 1982: “Roxy’s remarkable decade saw the band combining the sublimely melodic with the strangely experimental, lending a suave sensuality to nerdy art-rock (and proving that oboes can exist on a sexy rock record). Thousands of punk, New Wave and college-rock bands were shocked into action by Roxy’s early records, while sophisticated pop stars and new-romantic bands took their cues from their later hits.”

The band’s importance has never been a question for fans and indeed for other musicians. So the biggest question for most is why the heck had Roxy never, ever been considered for the Rock Hall. It’s a question Ferry tackled in an email interview to discuss the group’s history. (Note that he uses British spellings for some words.)

Q: Where are you as you’re answering these?

A: In Cape Town [South Africa], where I begin a tour tomorrow which will then take me to Australia, New Zealand and Japan.

Q: You’re the one who instigated the formation of the band, so it had to be your vision that drove it. Can you explain what that vision was?

A: After art school I began to feel that the best way forward for me as an artist was via music rather than painting. I had a real passion for it.

At first, I wasn’t entirely sure what I was looking for, but I knew I didn’t want it to sound like any other band. I had been listening to a wide range of music from an early age – jazz, rhythm ’n’ blues, “art” music – all sorts, and I was keen to reflect these influences in my own work. I set about trying to find like-minded people who might share my interest in exploring diverse musical styles.

I had a few songs that I’d been rehearsing with the bass player Graham Simpson, who had played in my college band, and these songs eventually formed the basis of the first Roxy Music album.

A friend of mine introduced me to Andy Mackay, who was also into experimental music, and who had his own synthesiser, which was quite rare in those days. Andy also played oboe, one of my favourite instruments, as well as saxophone, and this added an extra dimension to the music.

Not long after, Brian Eno brought his tape machine to record what we were doing, and he stayed on to join the band as synthesiser operator and sound mixer. He became a really important part of our sound, adding layers of sometimes pre-recorded tapes, and using the synth to treat the instruments. The unusually versatile guitarist Phil Manzanera and the powerful rock drummer Paul Thompson completed the band.

Q: The “art school background” you and others had has often been cited as the foundation for Roxy Music – in its sound, in its look, in its essence. How did that background manifest itself in Roxy Music and later, in your solo work?

A: My four years at art school helped to give me a sense of who I wanted to be, and how I wanted to live. You could say it was a formative period. It was inspiring for me to be in such a creative environment, surrounded by so many people all striving for self- expression. Up till then I had lived at home, and when I got to college, I was bombarded with lots of fresh faces and new ideas.

The famous pop artist Richard Hamilton was teaching there at the time, and his intellectually disciplined work and hip/cool aesthetic had a profound effect on me and my contemporaries. Images of pop culture from magazines, movies and consumer advertising became integral sources of inspiration for us, and I was drawn very much to the collage techniques of Hamilton and the American artist Robert Rauschenberg.

[Marcel] Duchamp was another name on everyone’s lips at the time, and his will o’ the wisp contrariness had an effect on some of my music, such as when I began doing my own versions of other people’s songs, an echo of his “ready-mades.”

The first Roxy album was very much a collage of musical colours and textures, and we found it exciting to jump from one thing to another, sometimes within the same song.

Q: Speaking of art, what’s your favorite medium? I know you’ve taught ceramics, etc. And do you have a favorite piece?

A: As a student, painting was my medium, but I stopped painting as soon as Roxy came together. There was never enough time to follow both callings. Designing the album sleeves then became the focus for my visual creativity, working together with a series of photographers and the fashion designer Antony Price.

The first Roxy Music album cover is probably still my favourite. I remember seeing a display of LP sleeves in a record shop window on its day of release, like a group of Warhol multiple images, and I thought how great it was taking art onto the street.

Q: What made you choose music over art?

A: Well, there are a few reasons. The physicality of music is one. In 1957, I was lucky enough to win some tickets to see Bill Haley and the Comets on what was the first rock ’n roll show that came to the U.K., and then in 1967, when I was a student, I saw Otis Redding with the Stax Revue; so I saw at first-hand what a powerful force music could be.

I liked the idea of being able to reach a wide audience with my work, and in the 1960s the art scene was more elitist than it is today.

Q: How do you translate a visual medium into a sonic one?

A: With great difficulty! I guess close your eyes and hope for the best…

Q: I’m not sure how many people are aware of your connection with Robert Fripp and King Crimson. How did that relationship begin and develop?

A: Before Roxy got started, I went to meet Robert Fripp and Peter Sinfield when they were looking for a singer/bass player to join King Crimson. I think they liked my singing but unfortunately, I couldn’t play bass!

A few years later Fripp played on one of my solo records, and Peter Sinfield produced our first album. Crimson introduced me to EG Management, who then represented Roxy for the next 10 years.

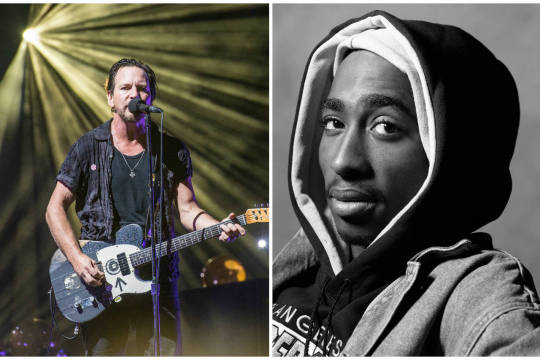

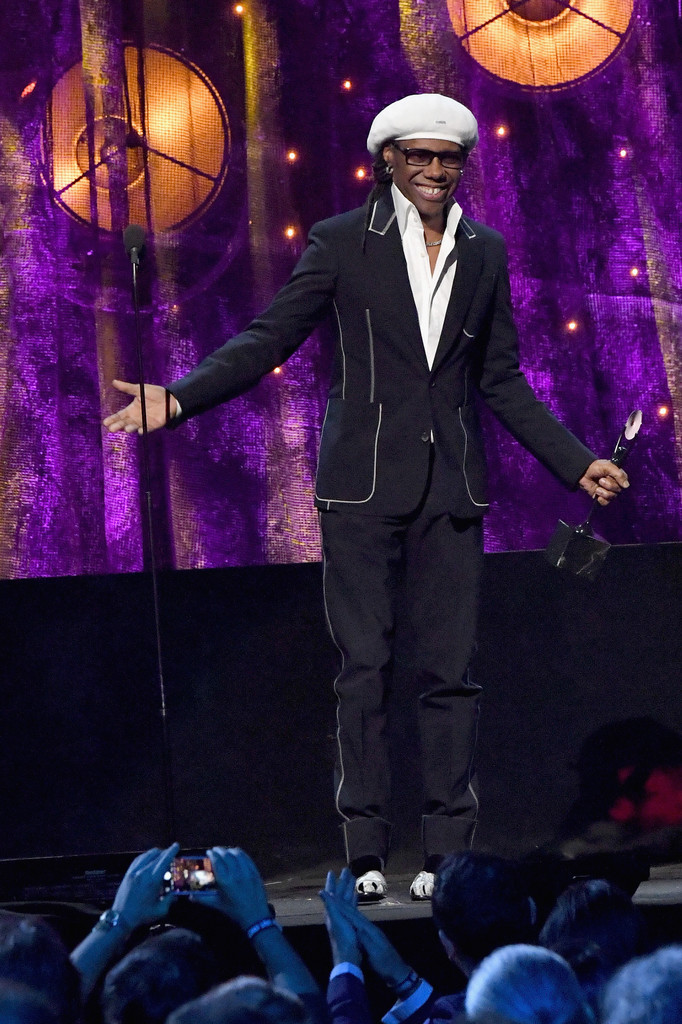

Q: A writer for the Guardian once said Roxy Music is the most influential British band after the Beatles. Along those lines, I just did an interview with Nile Rodgers, a Hall of Famer himself, who said, “Without Roxy Music, there would have been no Chic.” How do you react to statements like that?

A: I can see how Roxy Music pointed the way for some, just as we were inspired and influenced by many people who came before us.

Nile is an amazing musician who’s always been incredibly generous. I’ve had some great times with him in the studio over the years.

Q: “Avalon” is the album most people cite when they mention Roxy Music. What are your recollections of writing and recording the album?

A: I have many fond memories of that time . . . I began writing some of the songs at a remote place on the west coast of Ireland, where we eventually went back to photograph the album cover. We did some of the recording at Compass Point Studios in Nassau [Bahamas], and a bit of that island atmosphere made its way into the music, like the sound of the ocean waves on “Tara.”

Rhett Davies was the producer, and we mixed the record at The Power Station studio in New York with the great Bob Clearmountain. The final song to be recorded was “Avalon,” which became the title of the album.

Q: Is it the best album in the Roxy catalog in your mind?

A: I’m not sure it was the best, but there is a completeness about it that works, and a particular atmosphere. It was definitely a labour of love.

Q: The musical landscape in the 1970s was really confused, with bands like Led Zeppelin and Lynyrd Skynyrd vying with disco and pure pop. Where does Roxy Music fit in that kaleidoscope?

A: I’m not sure we did fit in. I think as the band developed, it became more subtle and suggestive, moody and atmospheric. So, in that respect, maybe it stood out from a lot of other stuff that was going on at the time.

Q: A band, a real band, is a collection of its personalities. They don’t always have to get along, but there is something about the chemistry that triggers creativity. Can you talk about your relationship with some of your bandmates, including Brian Eno?

A: Humour was an important element within the band. I seem to remember we laughed a lot. Brian and I were very good for each other, and we both had strong ideas. Of course, in any band there is always going to be some friction, and I think that’s essential for creativity. However, I can’t remember any big rows. The first album in particular was recorded in a very convivial mood.

Q: I have read that you’re not a fan of the term “glam rock.” How would you describe Roxy Music when it began, and the final stanzas?

A: No, we were always a bit embarrassed by the term, and preferred not to be categorized, and placed alongside other bands who might not share the same ideals, etc.

Q: Technology has really evolved since then. What would a Roxy Music 2.0 sound like if you put it together today?

A: It’s hard to speculate, but I suspect it might not have been as much of an adventure if we had had the technology of today.

Q: Every time there’s one of these induction ceremonies and former bandmates play together, fans hope for a reunion. Any chance of that?

A: No. I already have a full programme.